This edited collection aims to bring into conversation two fields of the social sciences: the emerging social sciences of outer space (Dunnett et al. 2017, Praet and Salazar 2018, Klinger 2019), and recent social science research on infrastructure (Larkin 2013, Harvey 2015, Hetherington 2018, Anand, Gupta and Appel 2018). It seeks to explore how insights from the “infrastructural turn” in the social sciences can advance scholarship of outer space, and vice versa. Existing research in geography, anthropology and sociology repeatedly stressed the importance of understanding Earth and outer space in relational terms and mutually constitutive politically (Sage 2016), psychologically (Ormrod 2017), philosophically (Praet and Salazar 2017), methodologically (Valentine 2016) and ethically (Kearns and van Dooren 2017).

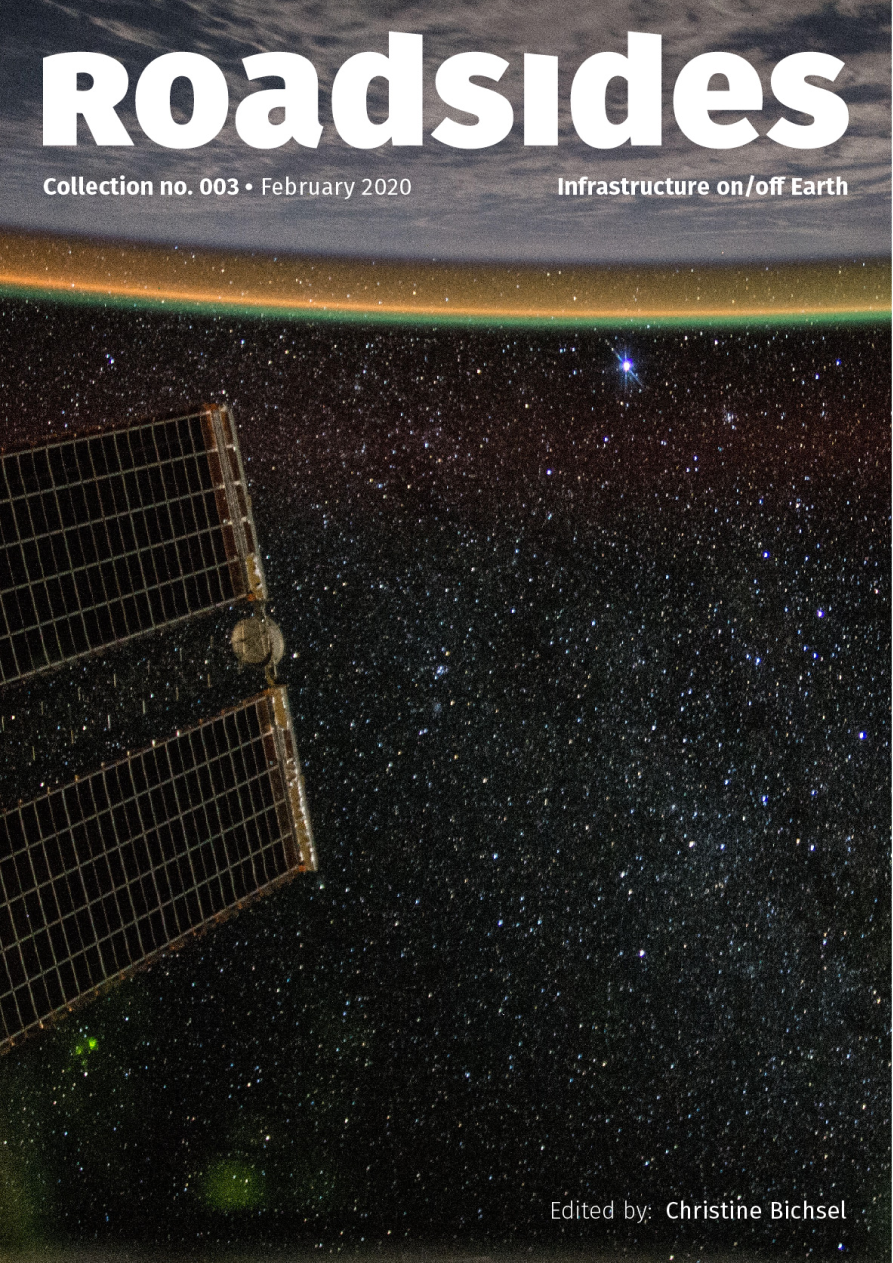

While infrastructure is a pervasive theme in much social science research on spacefaring and outer space, so far it does not figure as an analytical category in these works. The proposition of this collection is that an analytical focus on infrastructure to explore spacefaring advances our understanding of the relationality of outer space. Spacefaring is a highly material- and technology-intensive activity. Most of outer space can only be sensed through technology as a mediator, including radio telescopes, rover and satellite cameras (Vertesi 2015, Helmreich 2016). To escape Earth’s gravity, humans or non-humans require engineered vessels and strong propulsion produced by launching facilities (Valentine 2017). Once in space, they are fully dependent on a highly elaborate built environment, which creates the necessary conditions for survival under extreme conditions (Höhler 2010, Damjanov and Crouch 2018). Hence, this edited collection seeks to address the following question: How does the conceptual and empirical focus on infrastructure advance our understanding of the cultural, political and economic relationality of outer space?